Blog

Articles and opinions from the world of photographic collections.

Articles and opinions from the world of photographic collections.

Please see below the complete recording of The History and Identification of Photographic Processes, presented by Susie Clark at PCN on 30th April 2020.

PCN's current Featured Collection is from the Madame Tussauds Photographic Archive, we've been talking to curator Zoe Louca-Richards about the collection and her work.

PCN, Hi Zoe thank you for taking the time to be our Featured Collection can you tell us a bit about this collection, its history and your role working with this collection?

As curator I am responsible for an eclectic collection documenting the history of Madame Tussauds London, its formidable founder Marie Tussaud, and her family, who were integral to the development of the business until the 1960s. Day to day I provide research support for the brand, and manage a heritage collection containing everything from a pair of Elton John’s shoes, to Marie Tussauds’ 1803 letters. For the past 18 months it has been my mission to identify the unique treasures we have hidden away in cupboards and basements, and through them reinvigorate our remarkable history. The glass plate negative collection drew my attention early on for both its documentary and aesthetic value. A small portion of the collection had been digitised in 2015 along with early company documents and records, but otherwise had been largely forgotten.

At PCN we're very passionate about glass plates can you tell us more about this part of the collection?

The glass plate collection contains over 500 negatives, ranging in size and dating between 1890 and 1950. It provides a unique and unrivalled insight into the history of the Madame Tussauds attraction in the early 20th century and is a valuable resource for understanding the history of the company. The collection is thought to have been solely the work of John Theodore Tussaud, the great grandson of Marie Tussaud, and creative director/head sculptor of Madame Tussauds in the early 1900s. The John Theodore Collection is part of this broader collection, and comprises 3 wooden boxes containing 120 negatives, dating from the mid-1890s – the earliest in the entire collection. Unlike the rest of the Madame Tussauds glass plate negatives, which have at some point been rehoused in contemporary conservation wrappers and boxes, this small collection has remained in their original indexed 19th century negative boxes. This discreet collection of negatives differs from the broader Madame Tussauds glass plate negative collection as it contains not only early portraits of staff, but also family portraits and holiday snaps. It provides a unique and intimate insight into perhaps the second most famous Tussaud, and the reticulate work and family life of the man that saw the sale of the company out of the family, it’s survival through WWI, and a devastating fire that nearly entirely destroyed the company in 1925.

What content does John Theodore Tussaud's glass plate negatives cover? And do you know anything about his interest in photography?

John Theodore’s portraits, both in the studio and at home, exhibit a natural dynamism of pose and expression, distinct from the formal photographic portraiture of the late 19th century. Many believe that the snapshot only has an effect if we have a personal connection to it. However John Theodore’s snapshots of his children have a haunting, mesmerising, aesthetic beauty about them that grips the viewer, and evokes feelings of nostalgia and childhood innocence. These family snapshots and studio portraits all exhibit John Theodore’s exceptional ability to breathe life into static images, the very same skill that enticed the public so strongly to his wax portraits and Tableaus at Madame Tussauds. It’s hard to say whether he considered his photography as an artistic endeavour, or purely a documentary tool. Despite being a prolific photographer and his clear aptitude for the art, there are no examples of John Theodore ever discussing his photography. However, these photographs are the only remaining examples of his artistic talent, as most of his sculptures were lost in the 1925 fire and later the 1940s bomb.

Amongst the beautiful but haunting snaps of his children playing in cottage gardens, energetic studio portraits, and aesthetically pleasing landscapes of the English countryside, are a number of blurred or over exposed images. To the contemporary eye, these are the abject images that would be swiftly deleted without a second glance in today’s digital world, but John Theodore preserved and indexed them equally. These fascinating images demonstrate someone grappling with how to master this relatively new technology, for both the benefit of his work, and his family record – finding value in both success and failure. John Theodore was an innovator, much like his great grandmother, with several registered Patents to his name, and whilst we cannot say if these “effects” were deliberate or mistakes, these images are a fantastic demonstration of the creative and experimental approach John Theodore was known by his friends and colleagues to take to all avenues of his work, whether in art or in business. Photography is of course now a significant part of the sitting process for creating our figures at Madame Tussauds, and John Theodore was most certainly the first Tussaud sculptor to utilise this new technology as part of the process.

How has working with this collection impacted on Madame Tussauds the attraction?

The collection is helping to deepen our understanding of the attraction at the turn of the 20th century, a time of immense change for Madame Tussauds, and of John Theodore himself, the driving force behind its continued success during this period, and an integral member in what could be considered one of Britain’s most prolific artist families. So far the cataloguing of the John Theodore Collection has been relatively straightforward thanks to the meticulous indexing undertaken by John Theodore himself, and his wife Ruth. Both the larger Glass Plate Negative Collection , and the discreet John Theodore Collection, not only provide staff with a visual insight into the attraction, but also the opportunity to learn more about the members of the family who founded and ran the attraction for over 200 years. The hope is that eventually all of the negatives will be digitised and catalogued, so that this incredible resource can be used and accessed to its full potential.

You see more images from this archive on our Featured Collection page, and you can read more about the Madame Tussauds Glass Plate Negative Collection, the John Theodore Tussaud Collection, as well as other items from the Madame Tussauds Archive by going to https://www.madametussauds.com/archive

Ben Reiss is the Morton Photography Curator at the National Trust for Scotland, where he works to preserve, research and raise the profile of the c.50,000 photographs held at Trust properties across the country. Ben undertook a museums traineeship at the Wordsworth Trust and has worked with ceramics at the Middleport Pottery in Stoke, planes at Brooklands in Surrey, and fossils at the Hunterian in Glasgow. He helped install the Science and Design galleries at the National Museum of Scotland and worked on the Trust's Reveal cataloguing project before moving into his current role. In this blogpost, he tells us about the Morton Photography Symposium that took place at the beginning of this month.

On Tuesday 9th of April, the National Trust for Scotland held the first Morton Photography Symposium at Broughton House and Garden in Kirkcudbright. Inspired by the photographic collection of artist Edward Atkinson Hornel, and supported by the Morton Charitable Trust, this symposium brought together academics, museum professionals and scholars to hear papers on the subjects of The Camera, Colonialism and Social Networks.

The first panel of the day was concerned with western representations of the 'other', whether people or landscapes, as Hornel's photographs and paintings relied very heavily on using imagery of the 'other' to create idyllic and exotic fantasies.

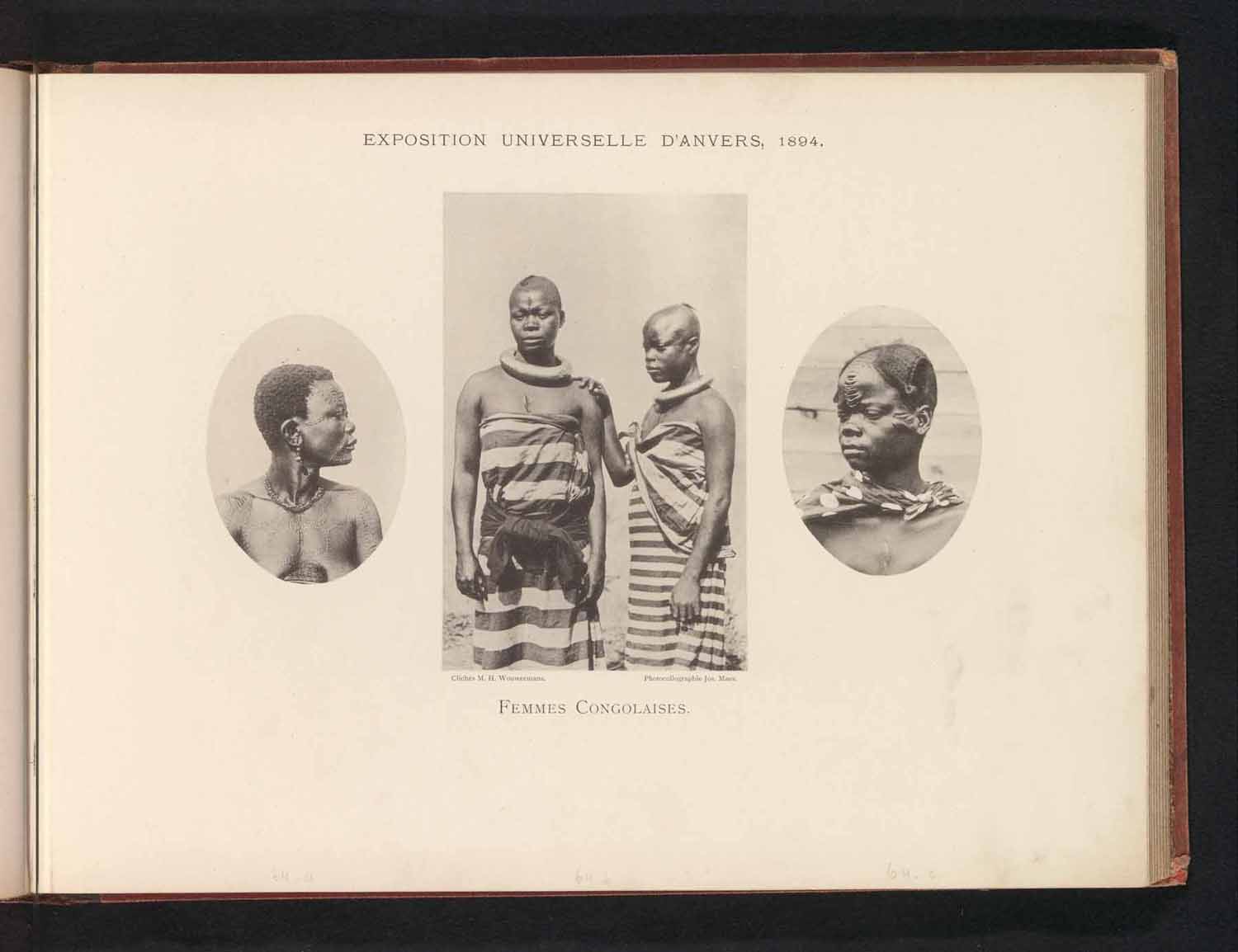

Two Portraits and a Double-Portrait of Congolese Women, Hippolyte Wouwermans, c.1890-c.1894, RP-F-2001-7-1487-64 – Rijksmuseum

Maria Golovteeva (PhD candidate at the University of St Andrews) explored some of the photographs taken at the 1885 and 1894 Antwerp international exhibitions. 1885 marked the start of Belgian king Leopold II's rule in the Congo, and the Congolese deputation at the 1885 exhibition was treated with respect and dignity, something reflected in statesmanlike photos taken of one of their number, King Massala. By the 1894 exhibition, Leopold's regime was committing regular atrocities in the Congo, and photographs of Congolese present at the exhibition reflect this change in attitudes. They were made to live in a fake village where they had to undertake pointless tasks to illustrate their 'otherness'.

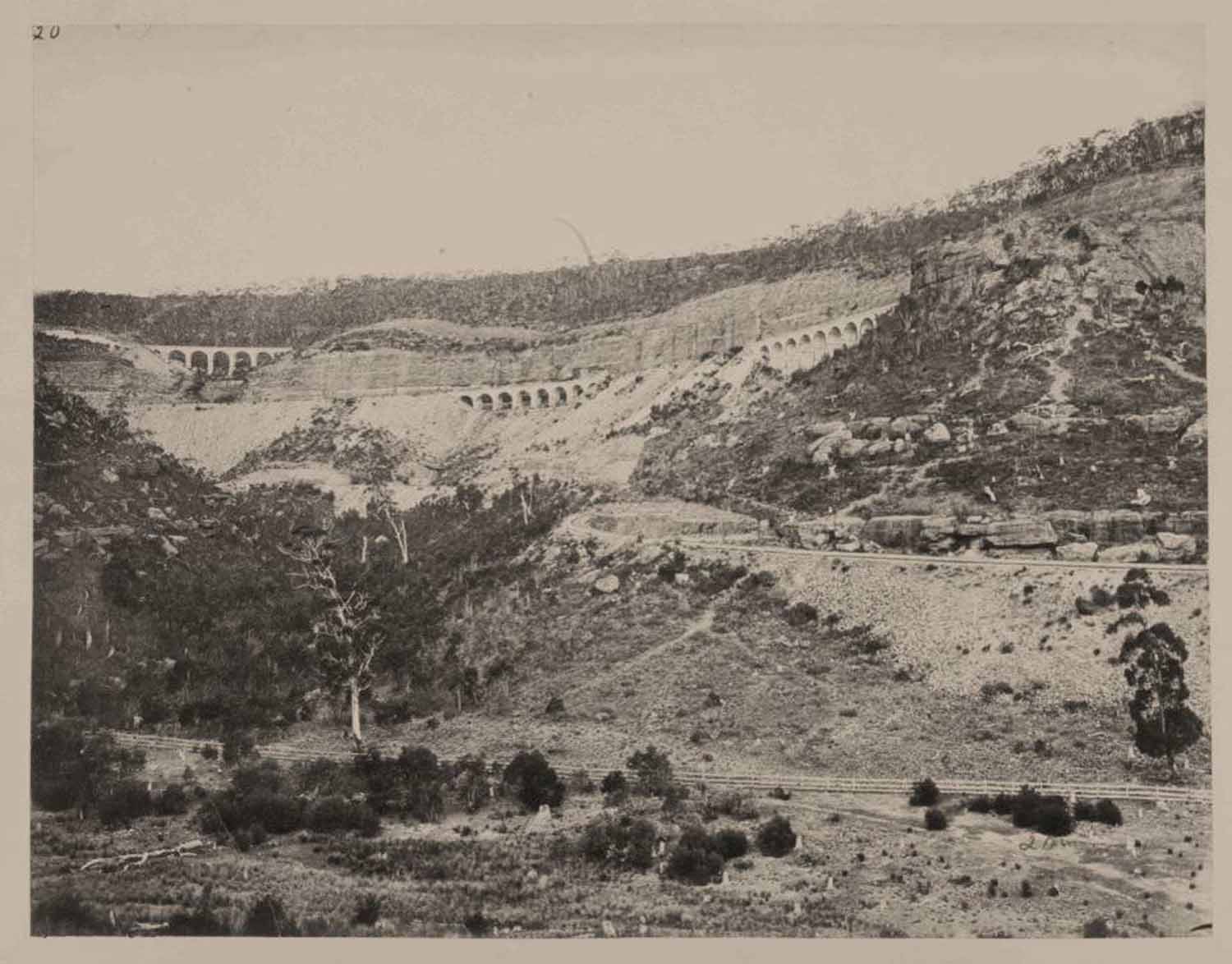

Sarah Hepworth (Deputy of Special Collections at the University of Glasgow) focussed on the way natural landscapes and feats of engineering in the USA and Australia are presented in photographs in the collections of the University of Glasgow. In the USA, these tended to emphasise the apparent naturalness of the wilderness, entirely ignoring the fact that many of these landscapes had in fact been carefully tended to by indigenous communities. In Australia, the emphasis was much more on western man's 'conquering' of the landscape through ambitious feats of engineering, once again ignoring the careful managing of the landscape previously undertaken by Aboriginal peoples.

Untitled, Lithgow Zig Zag Railway embankments and stone viaducts in Australia, unknown photographer, c.1870, Dougan 103 #4 – University of Glasgow Special Collections

In both papers were examples of how identities of either people or places can be constructed or erased through photography. Hornel also used his photographs to construct identity – that of the exotic eastern woman – while completely erasing the individual personalities of his models.

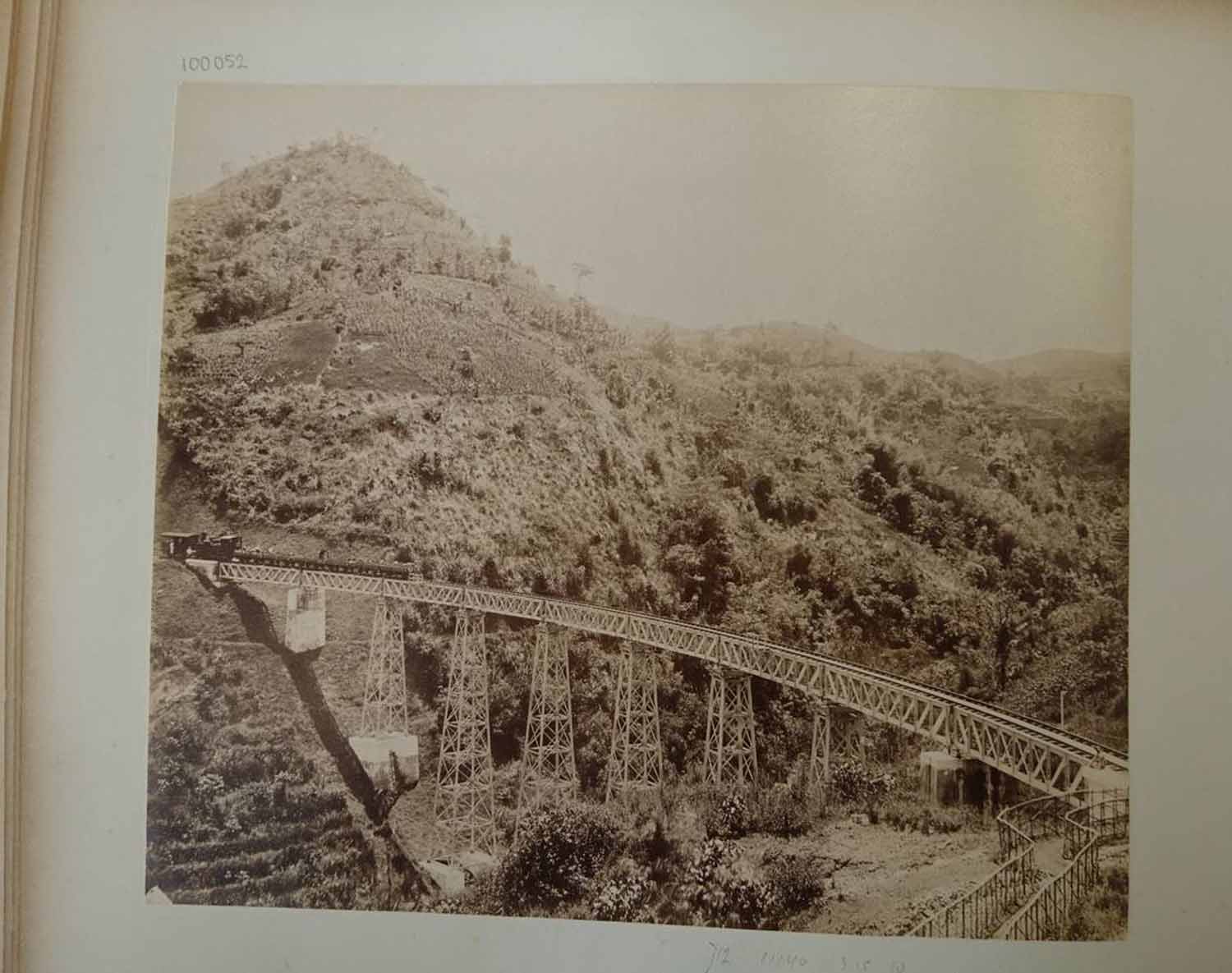

From the landscapes of American and Australia, the symposium moved on to those of Java and China. The second panel discussed the way these two Asian countries were represented and the networks that made this representation possible. Dr Alexander Supartono (lecturer at Edinburgh Napier University) took us through photographs taken on Java, and how these images were carefully constructed for western colonisers on the island, not the metropolitan elite who remained in Europe. He illustrated how crucial industrial networks (such as the network of sugar factories across the island) were to the growth and spread of photography across Java, fed by western engineers who wished to document their experiences.

Viaduct of the State Railway over Tjiherang in Preanger region, West Java, H. Salzwedel, c.1900, Collection Number 100052 in Alb-686: Donald Maclaine Campbell album p.11, KITLV – Leiden

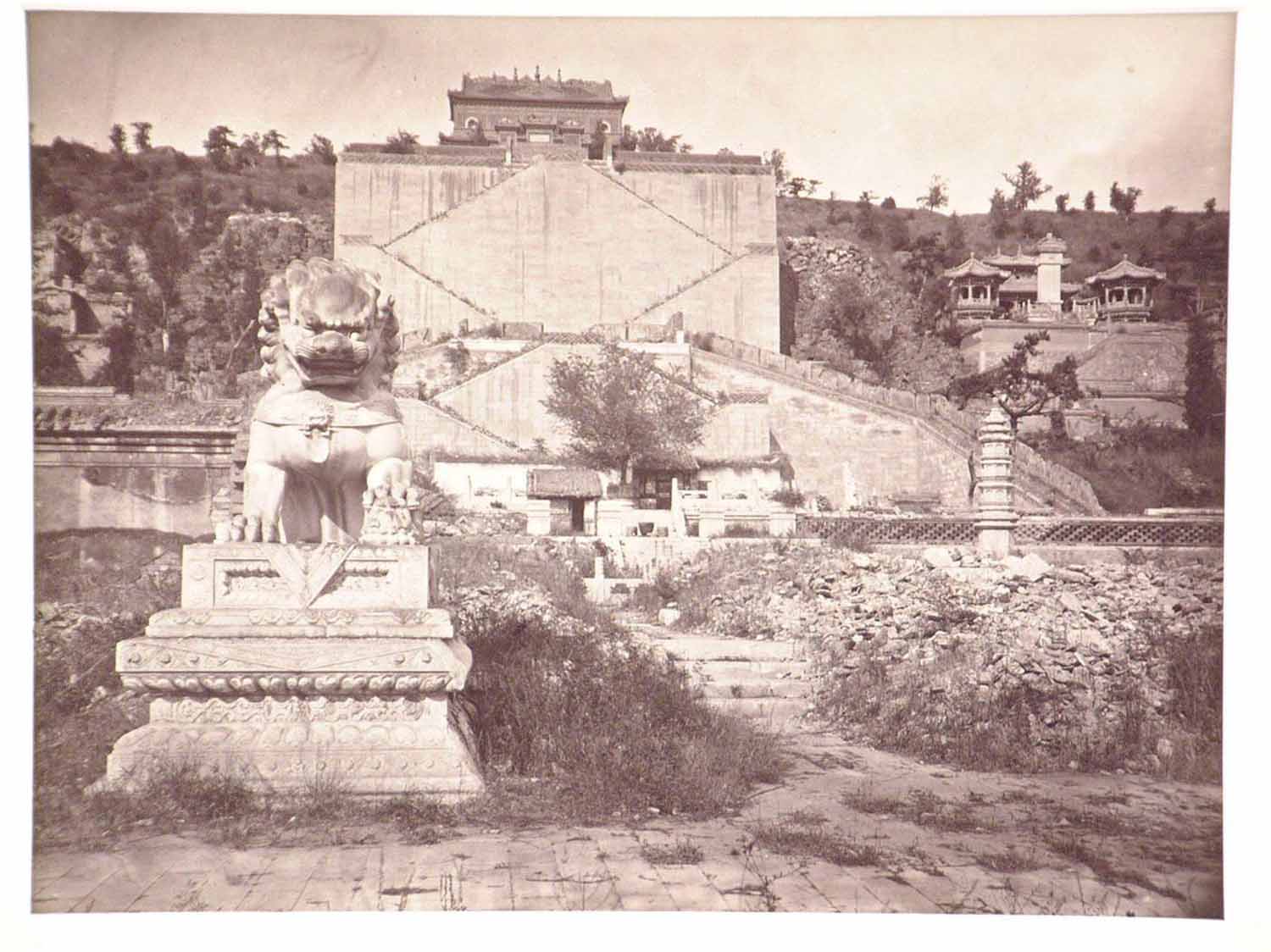

In China photographer John Thomson and missionary doctor John Dudgeon formed a friendship that further showed how social networks could influence photography overseas. Their relationship and its influence on photography in China was demonstrated by Professor Nick Pearce (Sir John Richmond Chair of Fine Art at the University of Glasgow), who concluded by positing that amateur photographer Dudgeon may well have shown professional Thomson (whose photos continue to influence our image of China today) where he could take the best photographs.

Hornel himself was heavily reliant on such personal networks (his cousin was a marine biologist in Sri Lanka) and more professional ones (such as the Japan Photographic Society) to take and collect his photographs, so it was fascinating to see examples of others sorts of western networks in Asia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

View of Wanshoushan from Lake Kunming, John Thomson, 1871, published in Through China With A Camera, 1898, facing page 246

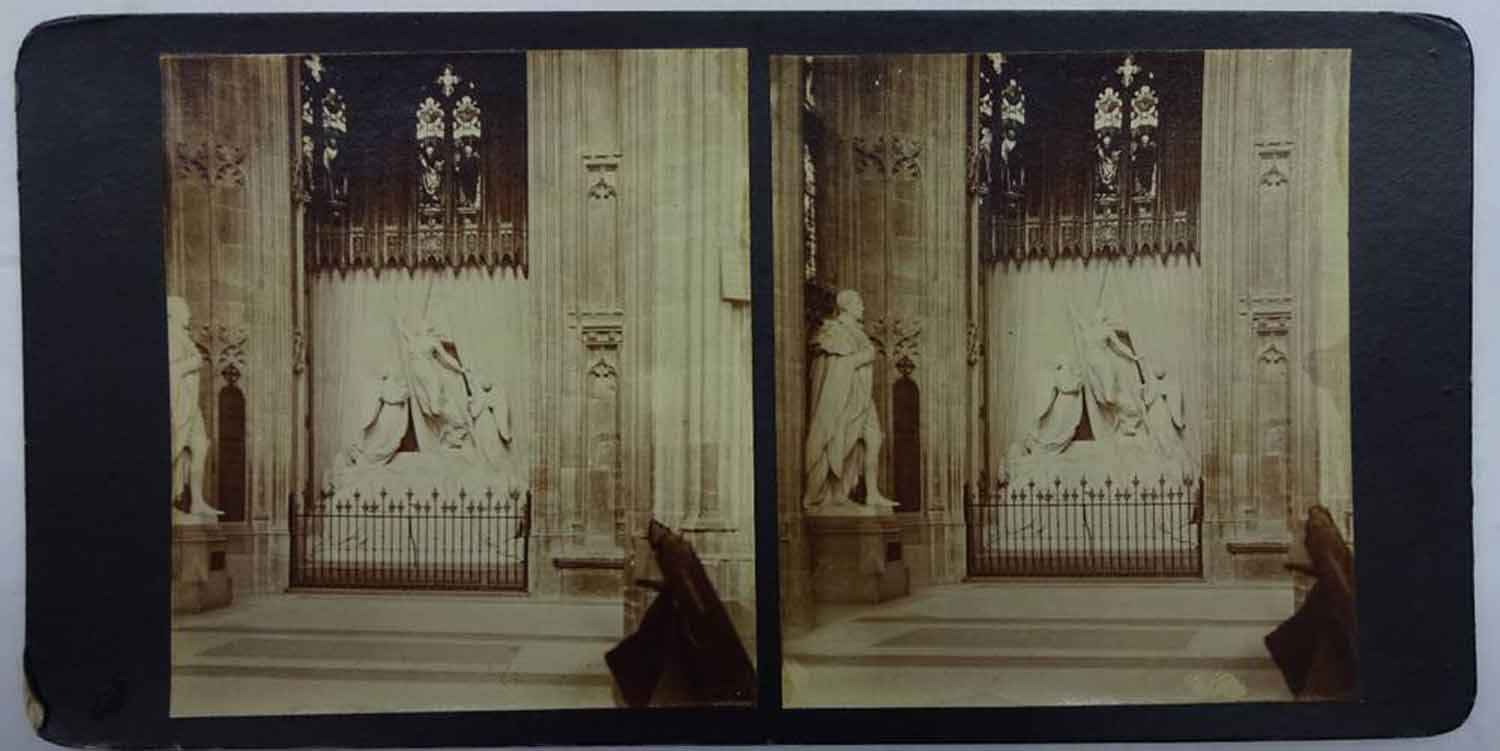

The theme of networks continued after the break with papers by Julie Gibb (assistant curator at National Museums Scotland) and Rachel Nordstrom (Photographic Collections Manager at the University of St Andrews Library, Special Collections Division). Julie introduced the United Stereoscopic Society (USS), who took and exchanged stereo cards throughout the first half of the twentieth century. They would write comments on the stereo cards of other members, much like a comment feed below an image or video today. Exchanging images was very important to Hornel as well and we have letters from him asking other artists to send him photos of particular subjects.

Stereo card of Princess Charlotte's Memorial, J. W. Vaisey, 1920, NMS IL.2003.44.6.27.4 – Howarth-Loomes Collection at National Museums Scotland

Rachel explored a rather different set of networks. By mapping duplicate images across albums in the collection of the University of St Andrews, she demonstrated that early photographers used pre-existing scientific and academic networks to share ideas and images, something which directly contributed to the growth of photography in Scotland. The earnest and supportive opinions shared by these pioneers contrasted considerably with the jokey and critical ones written on the backs of stereo cards by members of the USS.

Sir H Playfair and Dr MacDonald (The Sick Baby), unknown photographer, 1855, ALB-6-131-1 – Courtesy of the University of St Andrews Library

The final panel of the day combined issues of representation with modern social networks. Jessica Lee (completing her degree at Glasgow School of Art) took us through the history of photographs of geisha, starting with the way they were photographed by and for male photographers – both western and Japanese – and including Hornel himself. However, with the growth of social media and explicitly feminist photographers, modern geisha are much better equipped to take ownership of how they present themselves. They no longer need to be shown as the subservient and exotic women that were marketed to western men, and photographs of them can now be much more honest and nuanced.

Two Japanese Girls Dancing, attributed to E. A. Hornel, c.1893-c.1921, 2015.1565 – Broughton House & Garden, National Trust for Scotland

Alice Strang (Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the National Galleries of Scotland) delivered the final paper on the contemporary artist Monster Chetwynd, who uses photographic images extensively in her work. Monster Chetwynd has used this work to build multiple subversive social networks that have been described as a 'goo' that links people together across the world. Photography is crucial to this, either appearing in collages or being used to capture and record the otherwise ephemeral performance pieces that the artist undertakes.

These papers led into an enthusiastic discussion about the impact of digital photography and social media on photography today. The general consensus was that these had been good for photography, making it a more democratic and accessible medium. However, concerns were raised that these modern phenomena risked devaluing the skill of professional photographers and that social media sometimes encouraged people to focus on taking photos of themselves rather than looking at the photos in front of them.

This discussion encapsulated how, throughout The Camera, Colonialism and Social Networks, it was illustrated how crucial social networks of all kinds have been to photography throughout its history, from the very earliest scientists to today's social media. This was particularly true for photographers working in what were for them far-flung corners of the globe. These photographers used their networks and the opportunities the camera provided to access and acquire images of 'exotic' people and places. Hornel took full advantage of this himself, and became the artist he did as a result.

Two Japanese Girls, E. A. Hornel, c.1921-c.1925, 5.30 – Broughton House & Garden, National Trust for Scotland

To coincide with this month's Featured Collection of images from FORMAT19 FOREVER//NOW, our members' blogpost this month featured a talk given by our director, Paul Herrmann at this year's festival in Derby. In his talk, Paul discussed how through the work of the PCN, some worrying patterns about the the issues people and organisations were facing specifically about digital work began to emerge.

The early days of digital promised something amazing: using the power of the link, no less than an interconnected and interwoven visual story of our era; the idea of the photograph as a node in a living network. But the reality, and the early conclusion of our research, based on interviews and surveys, is that that might not happen. If we do nothing, we will get a very skewed digital legacy. How will we access today’s born-digital photography in 100 years’ time?

I’m going to talk about three areas - personal photography; small private archives belonging to photographers, galleries and SMEs, and larger public collections. They have different but overlapping problems. And I’ll finish with a few examples of where the problems are being tackled, and some suggestions.

Personal photography

About 10 years ago an elderly relative of mine died. The man's daughter and son-in-law took it upon themselves to sort things out in the way that is considered necessary when somebody dies. The son in law rang me up a few days later. He said: "I've cleared his computer and sold it."

Nobody now knows exactly what was on the computer. I imagine it included emails, writings, ideas, inventions, photographs, documents. What I might call my relative's "creative output". And, by implication, stories about his life; who he knew; whom he interacted with; what they talked about. It also contained things like caches, accounts, search histories; automatically-produced data that might tell a slightly different story about my relative's life. To quote the academic Kyle ML Jones: "Each of us has a 'data double,' a digital duplicate of our lives captured in data and spread across assemblages of information systems."

Most of us can immediately understand the difference between creative output and automatically-produced data. And a moment's reflection can tell us that the creative output is on a spectrum of privacy. It ranges from stuff that we are happy to share with the whole world, to things that we would really like to keep private, or even destroy. To the son-in-law, the answer was simple. Delete everything. My relative was a private man; let him keep that privacy in death. Yet when we surveyed photographers on this question, most of them don't want that. Only a very small percentage said get rid of everything. Most people would like at least some of their work saved, kept together, and available to look at. I don’t want to say we should obsessively save everything, but we should consider how we will be perceived in the future.

Of course when someone dies, a lot of things connected to the legal status of their property change. We can no longer ask people what their intentions were, so it becomes more difficult to act according to their wishes; even assuming that their own wishes were sensible and wholesome. Unfortunately, the law is rather a complex but at the same time blunt instrument. If we don't leave a letter of wishes, or sometimes even if we do, things are probably not going to happen the way we want.

One of the causes of difficulties is that photograph are at an intersection; they are both personal data and creative output. According to the current data protection act: "'Personal data' means any information relating to an identified or identifiable living individual." Of course that includes a lot more than just pictures of people; it might mean anything that includes any references to human activity. To oversimplify, the default position has become to lump everything together and delete it as “data”.

At the same time, the legal burden on the organisations that store people’s photographs is changing. One thing they want to avoid is getting involved in squabbles with heirs and other interested parties. Most social media services will deactivate accounts of the deceased at the request of an immediate family member. Some, in particular Instagram and Facebook, have started to include memorialising options. Facebook, which has put a lot of effort into understanding its users’ drives and motivations, allows for a Legacy Contact with certain powers. But I can’t imagine Instagram wanting to become effectively a graveyard with a majority of accounts belonging to dead people; and of course by definition this is going to happen some day.

Most contractual arrangements are rendered void by death of one of the parties, and I don’t think the social media companies see themselves as required to look after this material for ever. I can imagine a time when social media services just start quietly losing this work. Although Facebook claims not to delete photographs, several people have reported that they can’t find old images, and sometimes it’s the links to those images that no longer work.

What is the long-term future of our digital assets on the apparently free services like Instagram and Facebook? Think of the example of GeoCities, once host to 40 million web pages, which has now effectively closed down. You might be thinking that this is not what we are here to talk about. These people casually using free social media services can’t expect their work to survive. But that is not the view of social historians or archaeologists, whose work depends on access to individual and personal material.

The IT Consultant Andréa Perrot is looking at this problem in more detail. She says that in practice “how people manage their own images leaves a lot to be desired. When people die hardly anyone passes on information about their digital assets to their next of kin, in particular photographic images.” Meanwhile, she says, "The average person believes the world around them is managing the huge amount of electronic data to a sufficient standard." But cloud services are effectively being expected to look after what she calls “photography landfill”, or “cloudfill,” incurring increasing financial and environmental costs, while the difficulty of accessing and wading through the cloudfill will effectively render it inpenetrable. Worryingly she says: “Does today realise how the future may see us as a ‘lost generation’?”

Someone told me: I am the only person in my entire family preserving photographic material, analogue and digital. I fear if I die it will all be lost.

Small private archives belonging to photographers, galleries and SMEs

So let’s look at what might be seen as the next stage up the preparedness scale - professional photographers, SMEs, small galleries, and so on. Probably quite a few of you in the room today. You are prepared to invest in your and your organisation’s digital legacy. Are people in that position doing enough?

I don’t think so. For the purposes of the research we are carrying out, we surveyed people who have a working interest in a digital archive or collection of photography - a mixture of organisation staff, individuals such as photographers and their heirs, and concerned volunteers. We heard from around 70 people. From the survey, 67% of respondents - two thirds - agree that there is a real chance that digital material might be lost from their collection in the future Just 30% agree that the digital material in their collection is likely to be accessible in 100 years time.

There are significant concerns around knowledge, standards and conflicting advice. Only 43% agree with the statement “It's very clear to me what needs to be done to preserve digital material long term”, and only 29% felt that they have access to an authoritative source of knowledge about the subject. Only 23% of respondents have sought knowledge and information about this from a professional association. Just 7% have referred to a set of standards.

Typical comments include:

“If there is a set of guidelines or standards I should be following I am unaware of it, and make decisions based on what other people do and advise, and what seems sensible.”

“Digital standards seem quite elusive ... file types, sizes, systems seem to vary considerably and change frequently along with the opinions that revolve around them.”

49 people answered a question asking what collection management, cataloguing, digital asset management or backup software was in use. 42 different software applications and packages were cited along with four bespoke or self-written systems. That’s not in itself a problem, if all those packages are doing the job; but my impression is they’re not - people are using what they know, or feeling their way. I’d argue that for those looking for a universally recognised package for setting up an image database - there isn’t one.

There are also substantial concerns around technology. The long-term viability of different storage methods and media is often questioned. People cite drive failure, redundant software and even bit-rot. And at least one person has mentioned the rather wonderful-sounding M-disc - M for millennial - a DVD-R made of stone, or in fact a stone-like substance, that is supposed to last for a millennium. £22 for a pack of 10, with one three star amazon review saying:

“I bought these for long term storage of photographs - so it's impossible to review until after I'm long dead. Apart from that they seem fine.” Reassuring stuff.

I don’t want to say those two issues of knowledge and technology are not important, but I also don’t want to dwell on them too long; because I think they are actually specific issues in a more general context, and at least theoretically, issues that have been resolved. One respondent said: “the problem is not the technology, the problem is money and resources.” That’s getting warmer, I think. We have a series of system problems.

As a way into these more difficult areas I’ll use another example from my own life. I have worked as a photographer since the 1980s. I was asked to find a photo of someone I took on an unspecified date some time around the turn of the century. No problem, I thought, everything is catalogued. What I hadn’t realised is that during the changeover from analogue to digital capture, my archive changed from contact sheets to scans to CD and DVD backup to hard drives. I had five different systems over a relatively short timespan. Mainly because I temporarily forgot about one of them, it took me two days to find the photo.

The point is, I am supposed to be fairly competent in this area. Even assuming my heirs are concerned about my photography, I can’t see that they are going to preserve those delicate interrelationships between the elements of my five systems. That takes, yes, time, money and resources, and also care, and some decisions.

My own system was effectively a closed one. But when systems spread across multiple places and owners, the complexity escalates. The basic problem is that preservation of digital assets is quite a complex system where everything has to work. I don’t know if anyone heard the memorable talk by Hester Keijser in Derby a couple of years ago, but she described how the further away in time we get from any system, the less comprehensible it is. So we need to make sure that we all have at least a basic understanding of our digital lives. One curator told me that she simply didn’t have the knowledge to deal with digital objects in her own collection, but she depended on IT colleagues. That is no longer really an option for us as digital humans, homo digitalis. Skills like keeping our operating systems up to date and maintaining our digital storage and backup are now as essential as knowing how to find a book in a library, or even, dare I say it, as crossing a road. As things are, we continue to hand over power and responsibility to technicians who, to be fair, probably don’t want that responsibility.

The role of all of us is to know at least roughly how our systems work and keep surveying and testing for weaknesses. Those weaknesses could be around knowledge standards and technology, but they could also be legal, political, commercial, or cultural. In other words we might lose digital assets because we don’t know how to preserve them, or because a bit of technology fails, but also because we have an inappropriate contract, or a new law comes in; there is a board or management decision to delete material or spend less money on keeping it; we outsource to a particular company that closes down; or for whatever reason it become appropriate to change policy. Or a million other reasons. It’s really important to keep actively looking at how a system is functioning rather than fall back on some procedures that might become outdated or not up to the task.

Larger public collections

Let’s look finally at some larger organisations, the institutions such as museums, libraries and big archives that we task with looking after our common heritage. They are system-based organisations themselves, and so somebody ought to be keeping watch in the way I described before. Are they the most prepared for this work of preservation and legacy access?

Sadly, I don’t think so. In fact their systems are creaking and cracking. I suspect it’s to do with the way big, especially public, services work, and how it can be difficult to stay flexible and responsive in the way I just mentioned. If someone accidentally breaks a filter in the swimming pool, that’s okay, it gets repaired or replaced, and everything is back to normal in a few hours. But if somebody accidentally switches a fan off in the server room, and various systems overheat and circuit boards fry, that’s less okay. There is no digital equivalent of sprinkler systems. Sure there are ways of retrieving files and there are backups but it depends on that all working well. Google “How Toy Story 2 was almost deleted” for an insight into how easily it can all go wrong.

I asked around at medium-sized museums about their software systems. Are the collection management systems, digital asset management, storage, backup, and web servers, all talking to each other properly? Are the database fields replicated across the different packages? For the most part, people I spoke to shrugged their shoulders. One person under the age of 30 understood how it all worked. One museum manager told me: “if you find a place where they’ve got it all working smoothly, let me know.” Another museum employee showed me a former darkroom where he had set up his own unofficial storage systems, because he felt he couldn’t rely on the council’s outsourced IT services.

Let’s talk briefly about those outsourced services. There are organisations that say they can do all your digital preservation services for you. The trouble for individuals and small collections is the significant cost; well into five figures for a single seat. Private organisations such as ISPs can and do go bust. I know this from bitter experience when it took Redeye four months to retrieve all its data from a failed ISP.

Meanwhile, a third of the world’s web and cloud assets are stored by one company, Amazon Web Services, in their S3 storage. I am told it is extremely reliable, but it has had very occasional outages and I slightly shudder to think what would be lost if Amazon were to go bust. The way our public museums and cultural institutions are being systematically run down and underfunded is a depressing reflection of our political system. Everybody wants museums to be great, progressive and exciting, but in an era that tends towards polarisation, it seems that only the most large-scale of them, or the new start-ups with different business models, can find ways to achieve this.

Relevant quotes from our survey:

“Even if you know what to do, it is impossible from an institutional point of view to get a REAL long-term plan that is also sustainable in terms of resources. A big problem is that the bureaucracy level that is at the top of institutions and gives us the money still believes in the digital revolution but doesn't understand that a lot of actually obvious measures still have to be taken, among them long-term digital preservation.”

“We are several sites that cover several disciplines, with several systems. Each department has evolved separate procedures for cataloguing digital assets.”

“It's often the people within the organisation who are decision makers on budget, that do not understand digital or the value of photography as historical records. This lack of knowledge or unwillingness to understand the value of digital records / images impedes the structuring, conservation and upgrades needed to store digital. Education is not just for the curator or archivist but for the finance and/or decision makers to supply necessary investments.”

I don’t want to end on a downer, because there are plenty of new examples of good practice, and there’s a few things we can all do to improve things. I like what is happening at the Martin Parr Foundation, which supports and preserves the legacy of photographers who made, and continue to make, important work focused on the British Isles. They are just starting to consider the digital assets of other photographers than Martin himself. They have three great things: a foundation legal structure that aims to preserve things well into the future; a flexible and responsive approach that has developed a really neat mirrored NAS system; and a very clever head of production Louis Little who oversees all that.

I was also pleased to hear from one photographer who has helped set up a shared, effectively co-operative storage scheme with 11 others in a similar position. The 12 people look after three mirrored servers in different locations. You buddy up with someone with whom you share your encryption keys. As with the Martin Parr Foundation there is trust involved, but it’s a way of both spreading the risk and allowing continued access to your work in the long term - even for your heirs after you die. He thinks the system might be overkill given the price and quality of S3, but who knows.

I’m also intrigued by some of the new models of distributed storage, which seek to do no less than upgrade the web and resolve many of the problems we have been talking about without changing the interface. Have a look at IPFS - the inter-planetary file system - they call it the permanent web.

Finally, a few suggestions:

With friends or colleagues, talk about your digital legacy, and do some risk assessment - what could go wrong?

Think about what your heirs will find when you’re no longer there. Is it all clear enough?

Organise your digital archive as much as possible.

Write a letter of wishes.

Consider the spectrum of privacy and find ways to label your assets accordingly.

Be, or become, a digital human.

If you have a boss, make the case to them for digital preservation and legacy.

Come to the event we are planning at the end of 2019.

Links for further information:

The Digital Legacy Association

Data Doubles

IPFS

Preservica

Martin Parr Foundation

The Digital Beyond

Photographers' Archive and Legacy Project

Further information about this year's Format Festival can be found here.

To coincide with this month's Featured Collection, we interviewed PCN member Alex Anthony, who gave an indepth insight to the life, work and archive of renowned fashion photographer and film director, Terence Donovan.

Alex Anthony is an archive consultant and curator focusing on photographic and fashion collections. Trained as a photographer, she has worked for and with archives, galleries, museums, contemporary artists and designers for the past decade. Since 2013 she has managed the Terence Donovan Archive, based in north London, working closely with Terence's wife, Diana Donovan.

The Archive was established in 1997, and is comprised of negatives, transparencies and prints from throughout Terence Donovan’s nearly-four-decade career. In addition to his negatives and transparencies, it has a large quantity of magazines, diaries, daybooks and other ephemera. The Archive aims to preserve Terence Donovan’s huge body of work and to share his images with fans and new audiences. It undertakes exhibitions (public and commercial), book and film projects and regularly assists students, researchers, historians and curators.

Can you tell us a bit about Terence Donovan and his career?

Terence Donovan was born into a working class family in Stepney and came to prominence as part of a post-war renaissance in art, design and music. His professional photographic life started at the age of 11 with an apprenticeship at the London School of Photo-Engraving. He left at 15 to become a photographer’s assistant, and following national service and a stint as assistant to the fashion photographer John French, he opened his own studio in 1959 at the age of twenty two.

Part of a working class influx into the previously rarefied worlds of fashion, media and the arts, Donovan’s iconoclastic and sometimes irreverent photography established a new visual language rooted in the world he knew best – the streets of London’s East End. Taking his models to bomb-ravaged wastegrounds or balancing them off industrial building sites, his gritty and noir-ish style was more like reportage than fashion photography. He worked for some of the most innovative and influential magazines of the time including Queen, Town and London Life and his images became emblematic of the era. Donovan both documented and helped create the much-mythologised culture of 1960s London, and was amongst the first wave of celebrity photographers, socialising with, as well as photographing, the actors, musicians, designers and models who came to represent the decade.

‘Thermodynamic’, men’s fashion for Man About Town (1961) © Terence Donovan Archive.

Fashion photograph for the Daily Mail (1960) © Terence Donovan Archive.

In the 1970s he concentrated more specifically on advertising photography and moving image work and by the 1980s much of his time was spent making award-winning television commercials and advertising campaigns alongside editorial work for cutting edge magazines and newspapers. Donovan was also a pioneer of the pop promo, most famously directing the iconic and much-imitated video for Robert Palmer’s song Addicted to Love (1986).

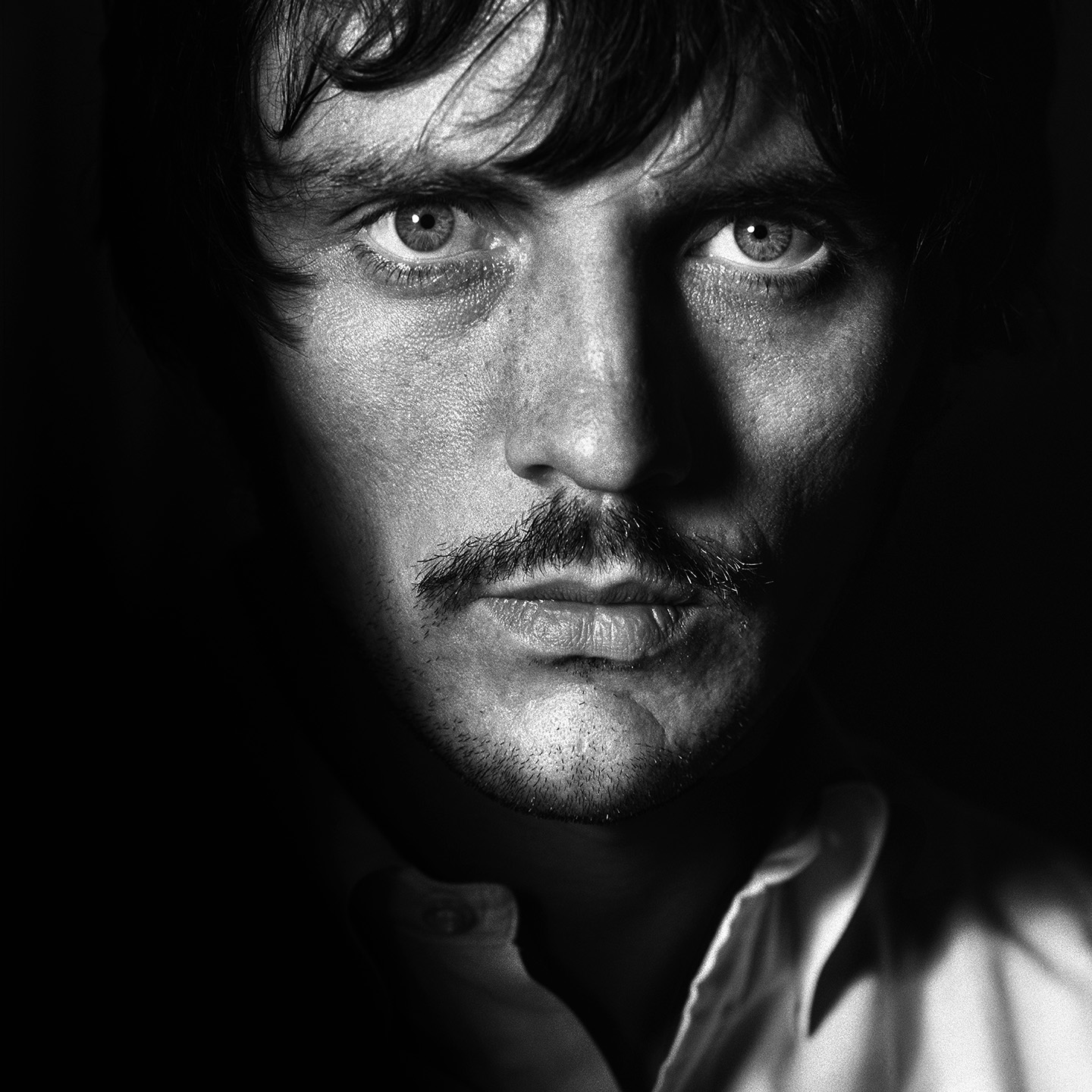

Terence Stamp (1966) © Terence Donovan Archive.

The late 1980s and 1990s marked a return to stills photography, with Donovan revisiting black and white film; his preferred medium during the early years of his career. He died in 1996.

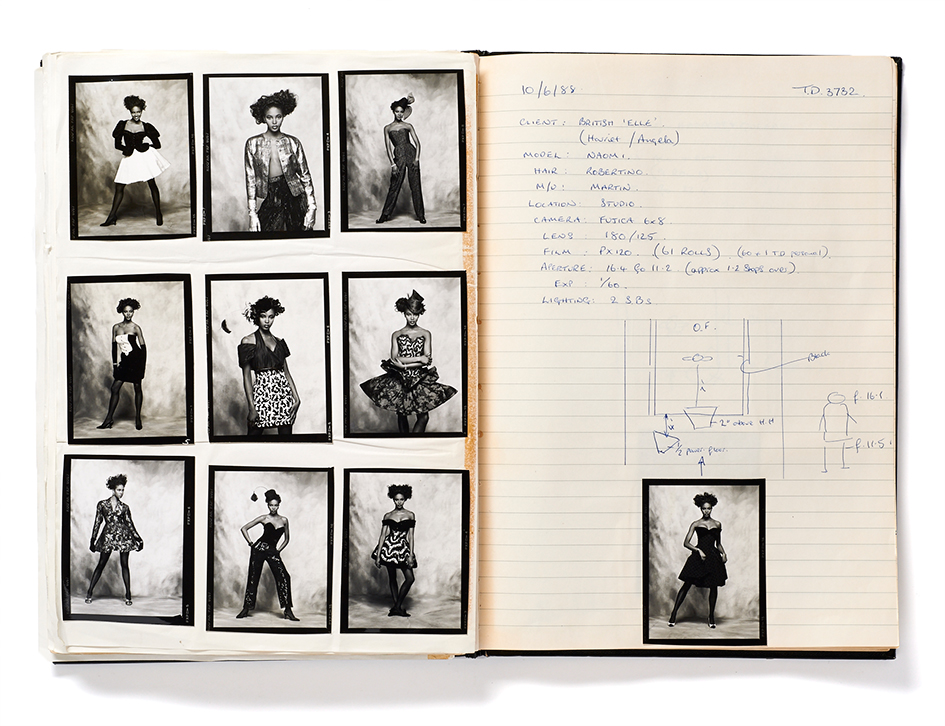

Naomi Campbell, Elle (1988) © Terence Donovan Archive.

How and when was the Terence Donovan Archive established?

The Archive was established in 1997, and is comprised of negatives, transparencies and prints from throughout Donovan’s nearly-four-decade career. We are based in north London.

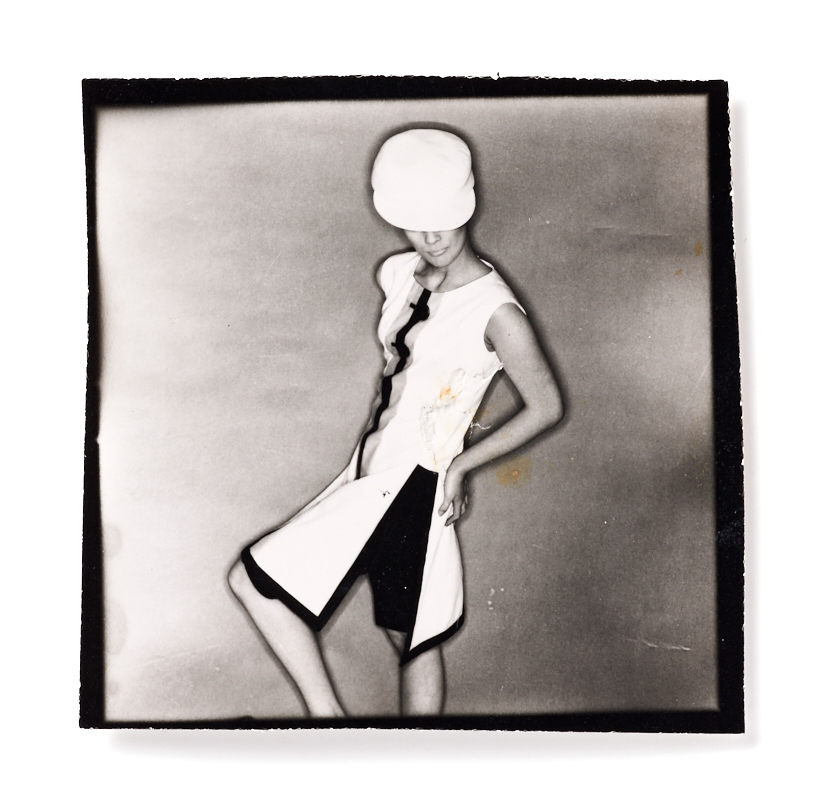

A vintage contact print of Celia Hammond modelling for Mary Quant’s Bazaar label (1963) © Terence Donovan Archive.

At the time of Terence Donovan’s death, the output of his photographic life was spread across various locations in London – his family home, his studio in Mayfair, another property in Bow in east London and miscellaneous other studios and printers. It is unlikely that Donovan would have thought of the material that he had amassed over the decades as an ‘archive’ or ‘collection’ in any formal sense. Although fortunately for us he kept his negatives, transparencies and photographs (including outtakes and test prints), he didn’t have any inclination to revisit past work – packets of 1960s negatives that were carefully fastened with string and boxed up shortly after they were taken weren’t re-opened again until his wife, Diana, asked the curator Robin Muir to undertake the cataloguing of the archive forty years later. Donovan viewed himself very much as a working photographer – his mind was always on the next job rather than on past achievements.

What material is in the archive?

Donovan was prolific and worked continuously throughout his career. He is most well known for his fashion and portrait photography - he worked for all major UK and international magazines including Vogue, Elle, Tatler, Harper’s Bazaar, Cosmopolitan and GQ and as well as undertaking commissions for cult magazines of their time Queen, Town and Nova.

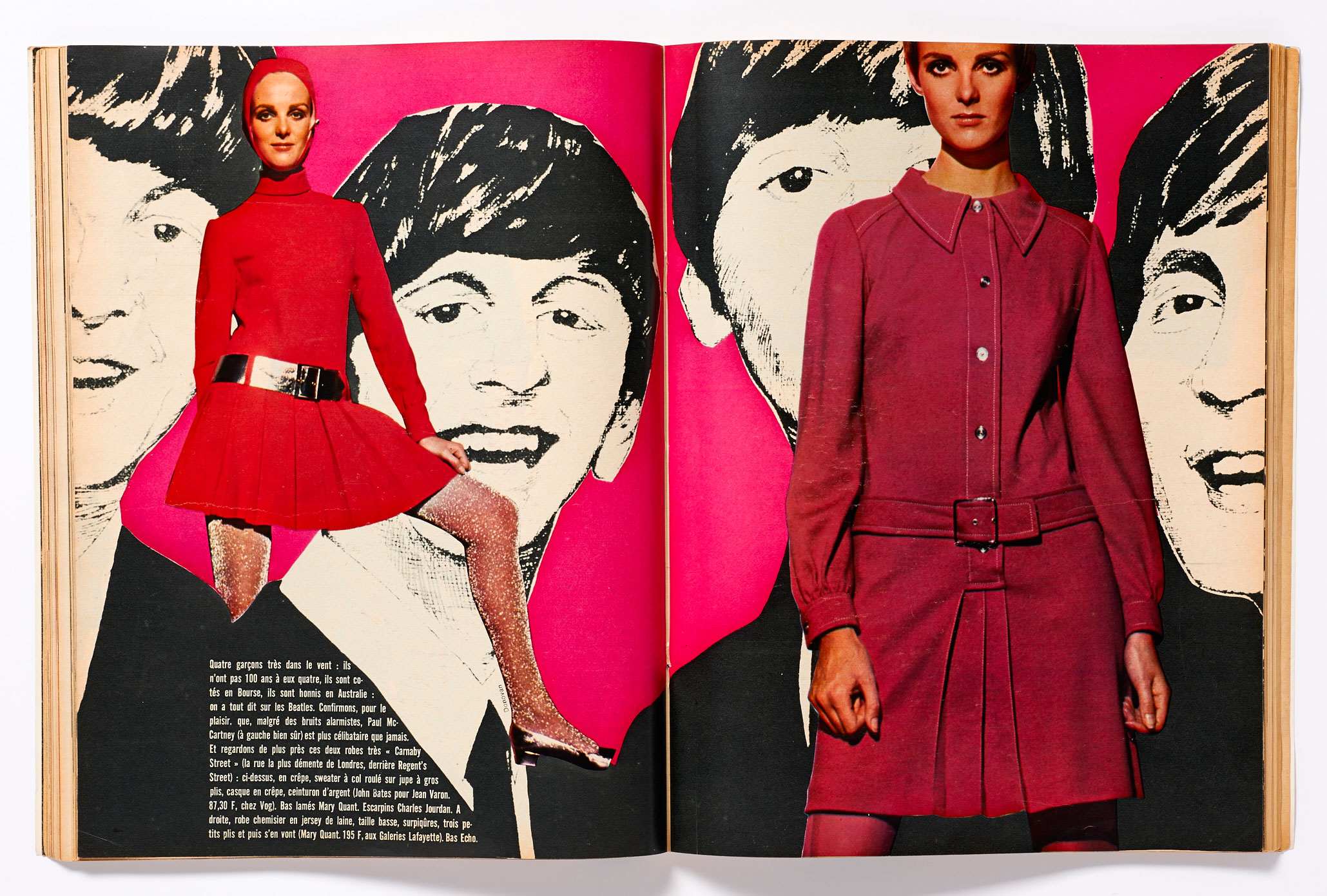

Grace Coddington, French Elle (1966) © Terence Donovan Archive.

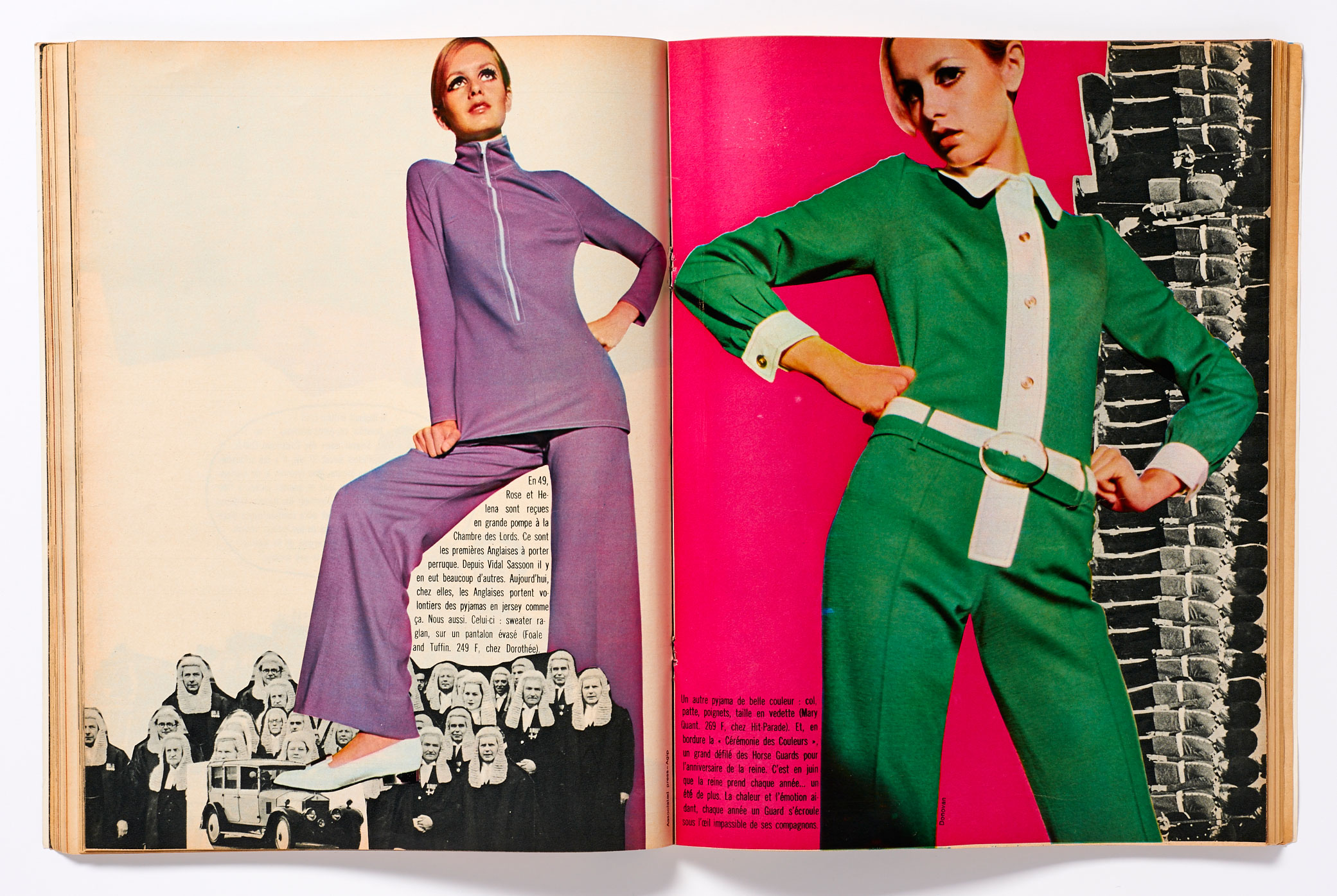

Twiggy, French Elle (1966) © Terence Donovan Archive.

We hold in the region of 800,000 negatives and transparencies in all film formats, though the majority are 35mm and 2 ¼ inch. Most of the photographs are silver gelatin prints. Donovan was an accomplished printer and had his own darkroom at home.

In addition to his negatives and transparencies, the archive has a large number of magazines, diaries, daybooks and other ephemera, which contain meticulous records of jobs undertaken and technical notes and provide a unique insight into his working life. They help us to pull together the stories behind some of his images (both in terms of where an image is positioned within Donovan’s body of work, but beyond that, what was happening in a wider social and historical context).

Naomi Campbell (pages from Donovan’s 1988 studio daybook) © Terence Donovan Archive.

For example, Donovan’s diary entry from August 1967, gives us the exact time (7pm) and location (flat 9, 43 Upper Berkeley Street) of his sitting with Jimi Hendrix. In contrast to the furore that surrounded his stage persona, Donovan’s portrait captures a quiet Hendrix at ease, swathed in and surrounded by the treasured colourful textiles he transported from home to home. This image, taken at a historic point in both Hendrix and Donovan’s careers, captures them at the very height of their respective powers. They were two iconoclasts, operating at the very centre of the swirling and overlapping social and creative scenes of 60s London.

Jimi Hendrix (1967) © Terence Donovan Archive.

What sort of activities does the archive undertake?

We stage exhibitions, contribute to group shows, books and films and regularly assist researchers, historians and curators. We are a self-supporting, private archive and so projects that focus on public engagement such as ‘Speed of Light’ (a retrospective staged at The Photographers’ Gallery in 2016), or group visits from fashion or photography students run alongside income-generating activities, for example selling exhibitions at commercial galleries and image licensing.

We are fortunate that Donovan worked very collaboratively and operated at the intersection of many different fields of specialism; not only photography but also fashion, portraiture, design, advertising and publishing. As a result we get enquiries on lots of different fronts – sometimes specifically about Donovan himself, at other times related to the subject of an image, the fashion designer of clothes he photographed or the groundbreaking graphic design of art directors he worked closely with such as Tom Wolsey (at Town magazine) or David Hillman (at London Life and subsequently Nova).

For example, the upcoming Mary Quant exhibition opening at the V&A in April will include Donovan’s well known 1966 shot of Twiggy wearing a Quant-designed moiré taffeta waistcoat and skirt, as well as his pared-back, black and white portrait of the designer herself, and magazine spreads from an October 1966 issue of French Elle in which Donovan’s fashion shots of Twiggy and Grace Coddington are brilliantly showcased by art director (and fellow photographer) Peter Knapp’s dynamic and colourfully collaged page layouts.

Mary Quant (1963) © Terence Donovan Archive.

Twiggy, wearing a Mary Quant ensemble (1966) © Terence Donovan Archive.

What is the aim of the archive?

In addition to the day to day tasks involved in working with and preserving a photographic collection (ongoing cataloguing, digitising and re-housing of materials etc.), and responding to enquiries from galleries, museums or publishers, we see a key part of our role as celebrating and sharing Donovan’s work and legacy. This is particularly true as he is no longer with us, and so it is the archive’s responsibility to balance what he may have wanted for his images with the demands of new audiences operating in a digital world.

For instance, on our Instagram feed we post ‘on this date’ images – photographs Donovan took on the same date in any given year. Many of the images are scans of the vintage contact prints that Donovan carefully reviewed, selected, marked up and kept with his negatives. Donovan would obviously never have imagined that these miniature reference prints would be displayed publicly. However, as an archive, we have made a decision to share them as we feel they enable a more personal connection to the man himself (by way of his handwritten annotations, crop marks and even the occasional inky fingerprint) and they provide an interesting insight into Donovan’s working process.

We want the archive to be a living resource which demonstrates the contribution Donovan made to British photography, is useful to people interested in the history of the medium, as well as fashion and design, and which also hopefully serves to inspire future practitioners.

Current and upcoming projects the Terence Donovan Archive has contributed to include ‘A Lifestyle Revolution: Swinging London’ on show at the Fashion and Textile Museum (8 February – 2 June 2019) and the Mary Quant exhibition opening at the V&A (6 April – 16 February 2020).

www.terencedonovan.co.uk

Instagram: terence_donovan_archive

All Images by Terence Donovan

Alongside this month's Featured Collection, we celebrate Chinese New Year with an interview with Open Eye Gallery's curator, Thomas Dukes, who offers an in depth insight into gallery's collection as well as the gallery's relationship with Artists of Asian Heritage and Liverpool's Chinese Community.

Could you give some background on the depth and breadth of the Chinese section of your collection?

We have over 1675 catalogued pieces making up the archive along with a number of other promotional materials such as magazines. There are some press prints in there and there's probably around 20 of the most contemporary possessions that I haven't actually popped into the digital archive yet.

The works in the archive that we could talk about as a lineage of photography relating to the Chinese community, particularly in Liverpool, starts with Burt Hardy's work from the 1940s looking at one of the earliest Chinatowns. Liverpool has the earliest Chinatown in Europe which is one of the reasons that as a photography gallery we're committed to working with people in Liverpool who have Asian heritage. This includes people in Chinatown who predominantly came from areas which are now referred to as the Guangdong region or the Hong Kong region as well as this new global citizen, the students that are at the four universities in Liverpool, who are all over China.

Bert Hardy’s work from the 1940s starts looking at the living and working conditions of people of South East Asian heritage who have come over to Liverpool. His work is black and white, it is documentary, it was primary taken for a number of the photographic journals such as The Life and Picture Post. It is a really early interesting piece that we are proud of having.

Shanghai restaurant, Nelson Street (1942) © Bert Hardy at Getty Images.

There are additional pieces alongside this but after that we skip forward forty-six years and there's Martin Parr’s collection of work entitled Connections which looks at the Liverpool-Manchester connection that featured photographers like John Davis. Martin Parr’s work also looks the relationship between Liverpool’s Chinatown and the Chinese community in Manchester and that was in 1986. This work displaced as part of Look 17. A couple of pieces from that collection that were shown over in the Museum of Liverpool which is a National Museums Liverpool property. That was part of an exhibition that was curated by a member of the team here, Charlotte Tsang. It looked at her selection from our archive alongside Chinese artists as well curated by Ying Kwok.

Sunday Afternoon, Liverpool Chinatown (1986) © Martin Parr.

Jumping ahead to Jamie Lau's commission from 2014. This was commissioned for the exhibition Urban Flow. I wasn't actually the curator here at the time, that was Joe Carruthers, and that's a really beautiful set looking at the contemporary Liverpool Chinatown.

Red Green and Black (2014) © Jamie Lau.

More recently, we've got Derek Mann from 2017. That was another Look 17 commission. Derek had this wonderful project where he'd gone back to Hong Kong and looked at the housing market over there. He grew up in Hong Kong and then moved to UK and he's now lived in both places for around the same amount of time and he's got to a point where he was looking at properties over in the UK and when he went back over to Hong Kong was able to make these comparisons about the global similarities when looking for property but also the accelerated nature of development over in Hong Kong.

From the series Close to Home (2017) © Derek Man.

Then finally there is Teresa Eng’s work in 2018. Her commission was part of Snapshot to WeChat. She made a project looking at the difference between the digital representation of self, as made through selfies or a shot of the person and their friends going out, compared to a portrait that was made of them there in the street and that was just phenomenal. That was between February 7th and February 14th in 2018, from Chinese New Year to Valentine's Day which was very cold time to be out in there, asking people if they would allow her to make a portrait of them as well as share their selfie!

From the series Self/Portrait, Liverpool (2018) © Teresa Eng.

The collection does hold this really fascinating history of engagement through photography with the Chinese community in Liverpool regionally, nationally and internationally.

Would you talk about the discussion that starts the acquisition of projects by contemporary artists with Asian heritage?

The discussion around acquiring a project or a group work is relatively standardised in that using guidelines from an artist's network and the Arts Council ensures that there's transparency and openness around the expectations of budget, for example, on both sides. Therefore, we just go into it saying, “we have X amount of budget and we would like to collect X number of pieces do you think this is possible?”. Recently all of the commissions that we've worked on in that way have been amazing. Thinking about Yan Preston, Derek Man and Teresa Eng, we've got this really interesting body of work that talk to issues that are as our as relevant on say, the Wirral, as they are in Shanghai or further afield.

The discussion that starts the acquisition of projects though predominately comes from the agendas within the gallery, given that we tend to work in partnership. For example, we will partner with Liverpool City Council to present a number of creative outputs or with city-wide festivals such as Homotopia or other National Portfolio Organization that advocates for social justice. So that the discussion around making a project will come from this kind of partnership work that we do around presenting in the gallery a series of events and work to inspire and start discussions and then this will grow into a project.

For example, with Derek Man looking at the rapid development of Liverpool and the rapid development of Hong Kong and what that means for a generation of people who are looking at having homes and making a project from there. Or, we have Yan Preston looking at the experience of an increasingly mobile citizen who is able to study in one place, work in another place and just becoming more familiar and the fact that there is a developing global identity and the discussion around it. They very much come from our work with communities around the gallery and then are carried forward into projects.

Echo (2018) © Yan Preston.

The gallery made a decision to "connect our collection to contemporary audiences through exhibitions and research”, what is your role in the process of connecting with the community as a curator?

This is entwined question. I always feel that the ethos in the Open Eye Gallery and the support of the whole team is what means that we are successful in working in partnership. It is no good if our responsive programming is working in partnership if I am not willing to be flexible around working with different partners and making the space somewhere that is accessible and usable. So, it's very much a team effort in ensuring that we can be a space for our audience.

In exhibitions such as North, a show that look at the generation of Northern character tropes as passed on through photography. For example, how John Bulmer’s image of 1960s girl with rollers in her hair coming over the Mill Bridge in Yorkshire gets updated into Alice Hawkins’ The Liver Birds shoot. We connect that to our audiences by sharing work in the collection that demonstrates how those tropes and photographic mores are onwardly communicated.

As a curator, I’d like to think that I connect with the community through talking to people and through working in partnerships. I can't be embedded in all of the communities we want to work with, but I can make sure we talk to people who are part of these communities. Making sure we are very open when we are communicating: when we are writing text and dialogue or when we are making a selection. It comes back to partnership and transparency and then being able to use the collection in a contemporary setting or against a contemporary concern.

You recently took a research trip to China, could you talk about how that was and the gallery's work with international artists more generally?

In the back part of September, I took a trip out to PHOTOFAIRS Shanghai. I was on a program that did our studio visits and institutional visits and I met a number of the collectors and artists and visited a number the galleries out there. I think for me, seeing how a cultural landscape is so different from here is just fascinating and it gives a much better insight into different ways that people engage with culture and the different ways that culture can be supported. It also raised questions about who are the most kind of active performers in making the culture, what kind of culture do we want and how we as actors inside it can work towards that.

At the moment, seeing the role of market forces in China is the most pressing thing for a number of the media outlets that report it. For example, The Art Newspaper and Art Review are quite concerned with market performance and the impacts of that for institutions and for artists. That is quite a large part of how the arts ecology can be supported, so seeing how the market is trying to find a way of ensuring that there is freedom for the possibility of experimentation but also making it so that being an artist is a viable career choice is interesting. I will be going out there again in December to meet lots more artists.

Working with international artists more generally, I think Look, our international Photography Festival, is the best way that we can do that. Right now, it is programmed in as a biannual festival and it's structured around using photography as a media of exchange between two countries.

Could I describe some of the work the gallery has done with local artists?

Liverpool and the North-West has a wonderful heritage to be proud of. We ha ve the Associates’ Network which is a collection of practising photographers, academics, critics, writers and people engaging with photography and an audience. We try and support them by being responsive to exhibitions in our reception area on the digital screen which is an open source space right now. We also place exhibitions more widely in places like the Victoria Gallery and Museum in the forthcoming Look. We try and be here for our creative audience, this is one of our target communities in Liverpool. We’re very contactable and very open; we have a number of events which allow for audiences to just come and form a relationship by spending time at the gallery, sharing interests and seeing if there are any opportunities where interests may align, that is the best way that we can work with local artists. We have a number of clearly defined routes through which local artists can come and be part of what we are doing.

How would someone go about accessing images in your collection? For example, how have others worked with your collection of the past such as Rosa Fong?

We do have a digital copy of the archive which has thumbnails and details but that's not publicly available. This is just because I still find today that when I'm contacting artists because we want to use their works that we hold in the archive in an exhibition, for example, or just generally we're in discussions, there are still some artists who say “I didn't realise that you know my work there” or “I don't remember how that happened”. So, it still feels like it's not as it's not as watertight as it should be. I don't think that that the quality of the images isn't such that it would allow for commercial use or only kind of marketable benefit to a third-party beyond education and ideas but still there's a few barriers.

For anyone who wants to see the archive they can just express an interesting and I can then write saying I'm happy to show the archive but accompanied by a clear warning as to the permissions and an agreement with the person that's it is for the purposes of education or development. The images can then be shared once the artist or the estate has been contacted. For example, Rosa Fong knew that we had the Burt Hardy pieces and so I sent over all of the images had a chance to look and we will then arrange a time where she can come in to look at the actual prints.

https://openeye.org.uk/

Twitter: @OpenEyeGallery

Facebook: Open Eye Gallery

Instagram: @openeyegallery

All Images Courtesy of Open Eye Gallery Archive

Introduction

With 2018 marking the centenary of the Representation of the People Act 1918, the Historic England Archive has undertaken a programme to make available to view online, collections of photographs created by women photographers.

While our rich collections are dominated by male photographers, we are fortunate to hold photographs created by women from the 19th to the 21st centuries, from skilled amateurs to professional staff photographers, including Alice Marcon, Margaret Harker, Eileen ‘Dusty’ Deste, Ursula Clark and our featured photographer, Margaret Tomlinson.

The Margaret Tomlinson Collection comprises nearly 3,500 photographic negatives taken between 1942 and 1963. The vast majority of which were taken when Margaret worked for the National Buildings Record, which had been established in 1941 to record historic buildings threatened by destruction during the Second World War. As with other images from our collection created by women photographers, some of Margaret’s work had already been digitised and made available on an ad hoc basis. Our women photographers project has enabled us to take a more strategic approach to conserving, cataloguing and digitising these collections.

25-36 Southernhay West, Exeter, Devon.

Historic England Archive BB42/00714.

Copyright Crown Copyright. Historic England Archive.

Photographed by Margaret Tomlinson after the Baedeker raids of spring 1942.

The skilled amateur in desperate circumstances

Margaret Tomlinson was born on 20 September 1905. She was educated at The Perse School and Newnham College in Cambridge, and trained as an architect. Margaret married her tutor in 1926 and had two children. When her marriage ended, she moved with her children from Cambridgeshire to set up home at Branscombe in Devon, where there were connections with her mother’s family.

In late 1941 Margaret contacted Edward ‘Bobby’ Carter, librarian at the Royal Institute of British Architects, looking for suitable work. A year before, Carter had been one of the leading lights in the creation of the National Buildings Record (NBR) and he wrote to its deputy director, John Summerson, recommending Tomlinson as a ‘good photographer’ and ‘v. nice competent person in rather desperate circumstances.’ Consequently, Summerson wrote to Margaret asking if she would be willing to photograph buildings for the NBR.

Margaret modestly described her photographic work as a ‘side-line’. She had been photographing architecture since around 1930, supplying photographs to a number of architecture and design journals, photographing for architects and had worked for an advertising agency. Margaret accepted Summerson’s offer and armed with her cameras, a permit to photograph on behalf of the NBR, a supporting letter addressed to the local police, petrol coupons for her 1936 Austin Seven and lists of buildings to photograph, she set out on fieldwork in January 1942.

Old Carpet Factory, Axminister, Devon, April 1942.

Historic England Archive BB42/00561.

Copyright Crown Copyright. Historic England Archive.

This image is listed in Margaret Tomlinson’s daybook as MT1, her first for the NBR.

A difficult start

Margaret’s initial forays into recording for the NBR did not run particularly smoothly. ‘Flu and a septic ear kept her housebound, and when she did manage to get out, the prospect of photographing scores of monuments in Exeter Cathedral, with limited winter daylight and restricted access due to continuing daily services, knocked her confidence. It was not until early April that she was able to make a new start photographing in Axminster, Exmouth and Exeter. In a letter of 4 May 1942 Summerson wrote reassuringly:

It is important in our job never to be in the slightest degree ruffled by the destruction of unrecorded buildings. The only thing to do is to plod along regardless of what happens.

Nelson Hotel, The Beacon, Exmouth, Devon, April 1942.

Historic England Archive BB42/00576.

Copyright Crown Copyright. Historic England Archive.

Baedeker and Exeter

A night raid by the Royal Air Force on the German Baltic port of Lübeck in March 1942 led to a new, retaliatory bombing campaign by the Luftwaffe. The consequences of which resulted in some of Margaret Tomlinson’s most memorable photographs.

Lower Market, Exeter, Devon, 1942.

Historic England Archive BB42/01177.

Copyright Crown Copyright. Historic England Archive.

This building was considered by the Ministry of Works as a chief secular cultural loss through enemy action.

The raid on Lübeck destroyed much of the town’s centre, tightly-packed with medieval buildings of historic significance. The response was to launch air raids against similar, relatively undefended cities in England and bring terror to their civilian populations. The cathedral city of Exeter, some twenty miles to the west of Margaret’s home in Branscombe, was one of the victims of what came to be known as the Baedeker raids, named after the German Baedeker guidebooks.

No 1 Dix’s Field, Exeter, Devon,

Historic England Archive BB42/00611 and BB42/00718

Copyright Crown Copyright. Historic England Archive.

Photographed by Margaret Tomlinson before and after the Baedeker raids in spring 1942.

Photographer and Investigator

In the summer of 1943, the NBR employed investigators tasked with undertaking extensive fieldwork to prepare lists of sites to be photographed. Because of her architectural experience, Margaret was asked if she would become an investigator for Cornwall, Devon and Dorset, and to combine this new role with that of photographer. Instead of being paid per negative, Margaret was offered a salary of £250 plus limited expenses to cover her role as an investigator and for 500 photographs, and six shillings for each additional photograph.

View towards the Church of St James, Slapton, Devon, December 1943.

Historic England Archive BB44/02155

Copyright Crown Copyright. Historic England Archive.

Slapton was one of a number of villages on the Devon coast evacuated in December 1943 to support the training of US troops for the invasion of Normandy

After the war

In January 1946 Margaret was offered a post as Temporary Investigator with the Ministry of Town and Country Planning creating lists of historic buildings. She was unsure whether to pursue this opportunity as she had concerns about the salary and the prospect of no longer working for the NBR, which had afforded flexible working conditions, and doubted her own suitability for the post. Margaret had also expressed the depressing nature of the monotony of the work and the negative psychological effect of witnessing so much destruction. After seeking guidance from Summerson, Margaret took up the position with a salary of £500. She continued to finish writing her NBR investigator reports, and mop up her remaining photographic jobs on Sundays and during periods of unpaid leave.

In the summer of 1950, with the Ministry of Town and Country Planning apparently having reduced its staffing, Margaret returned to photograph extensively for the NBR in Devon. However, cutbacks resulted in little more than requests for photographing buildings in imminent danger of demolition.

In 1954 Margaret moved from Devon to Little Easton in Essex, conveniently located between her Ministry office in London and her parents’ home in Grantchester near Cambridge. She remained at Little Easton during her retirement and published a history of her Devon family’s involvement in the lace industry in 1983. Margaret died on 9 October 1997, aged 92.

The back alley between terraced houses in Tunstall, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, 1960-2.

Historic England Archive AA64/00326.

Copyright Crown Copyright. Historic England Archive.

Margaret Tomlinson spent time in the Potteries in the late 1950s and early 1960s. She noted the ‘alarming rate’ at which demolition and rebuilding was taking place in the area.

Margaret’s work conserved

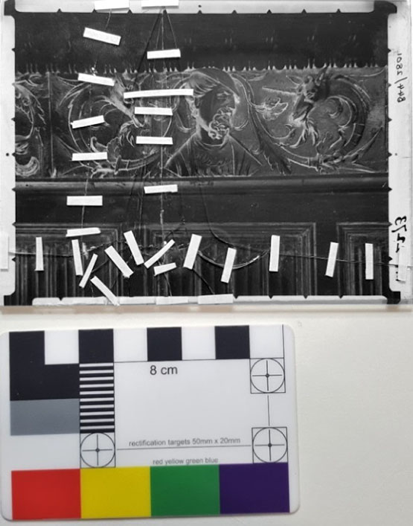

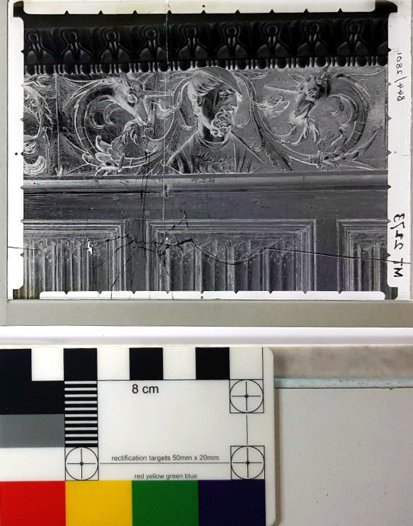

The Historic England Archive’s Conservation Department had to deal with 297 damaged Margaret Tomlinson negatives before they could be considered for digitisation.

In varying states of disrepair, 47 glass plate negatives were broken and a further 250 had become stuck to their enclosures, which had become embedded in the negatives’ gelatine emulsion (image layer).

Glass offers a wonderfully clear and undistorted carrier for the photographic image. However, chips, cracks and breakages in glass plate negative collections are not uncommon, with many collections suffering due to the inherent fragility of the glass support and more often physical factors attributed to poor storage and handling.

An enclosure becoming fused to the surface of glass plates is often caused by poor environment, such as being stored in a damp garage or loft. While a less common issue than broken glass, it is no less devastating to the condition of a collection.

Broken glass plate negative stabilised with

P90 tape prior to conservation repair.

The broken glass plate negative after stabilisation repair.

The cracked, broken and shattered negatives were conserved using a standard stabilisation repair, where the pieces are held in place using a card sink-matt and sandwiched between two sheets of cover glass in a pressure binding. This method is totally reversible; it avoids using adhesives and allows the negative to be digitised. It also provides a good long-term storage solution.

The negatives with the paper and cellophane enclosures embedded in the surface were a little more problematic. For these, a specific treatment was devised that would be safe and effective. A Preservation Pencil (a tool which produces a jet of very fine water-vapour) was applied to problem areas with control and accuracy. It was used to good effect to relax paper fibres and to soften adhesives used in the construction of the enclosures so as much of the material could be removed as possible.

Stuck glass plate negative in original housing materials.

Preservation pencil in action, working on stuck enclosure.

Glass plate negative after treatment and which can now be digitised.

All of this was painstaking work but incredibly effective, allowing almost 300 negatives to be preserved and digitised to reveal their secrets which would otherwise have been unusable, such was the damage.

The Margaret Tomlinson Collection can viewed online at the Historic England Archive.

Jenny Harvey

Archives Conservator (Photographic Materials)

Gary Winter

Exhibitions and Images Officer

An interview with Juliette Buss, Learning & Engagement Curator at Photoworks who led the collaborative ‘Into the Outside’ (ITO) project which supported young people in Brighton to engage with and create LGBTQ+ heritage. (Coinciding with Pride season, Into the Outside is the Photographic Collections Network 'Featured Collection' August - September 2018; find out more about it below.)

Hi Juliette, to start off, please tell us about your personal role in ‘Into the Outside’?

I devised the original project concept of creating a new archive with young people, then put the framework together with artist Helen Cammock and managed the project.

And how did this project come about?

We developed the programme as a follow on from Queer in Brighton a multi partner LGBTQ+ history project. Consultation with young people identifying as LGBTQ+ or U (unsure) revealed significant levels of anxiety, vulnerability and isolation. Brighton, the queer capital of the UK, has a vibrant LGBTQ+ community, but many young people just coming out, or questioning their sexual orientation or gender identity, weren’t yet part of this community, so couldn’t learn or benefit from the lived experience of others.

Which photographic archives were involved?

The group engaged with archives held at The Keep, a world-class centre for archives including Brighton Ourstory (set up in 1989 to collect and preserve lesbian and gay history) and the National Lesbian & Gay Survey - a collection of personal writing and ephemera submitted between 1986 and 1994 addressing issues such as coming out, homosexuality and the law, and the impact of HIV and AIDS. People of all ages contributed to the survey, but a significant proportion of writing by young people in their late teens, made it particularly relevant.

Tell us a bit about the partners and participants?

The project was led by Photoworks in collaboration with Brighton & Hove Libraries Services, the Mass Observation Archive, the East Sussex Records Office and Queer in Brighton and supported by the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund. Partners helped steer the project, and provided additional resources, expertise and capacity. We also engaged local (Stonewall Champion) schools. About 20 young people committed to the entire 18 month project - although we’re committed to working with LGBTQ+ communities long term and Into The Outside activity is still continuing in other guises including further youth projects, teacher training and through the online platform.

How were the young people involved?

The young people took part in an artist-led programme of photography and heritage-based activity with award-winning artist Helen Cammock, enabling them to create new work for two high profile exhibitions, run a series of events for other young people and create a new digital queer youth archive.

Their roles shifted quite dramatically through the project. As the project progressed, their knowledge and confidence grew, and their roles changed. They led interviews with other young people and ran pop-up photo studios and oral history booths. The participants also co-curated the final exhibition.

How did the project help young people build the skills to create a contemporary archive?

Artist Helen Cammock and the group started with skills development – oral history training, archiving and photography, plus conversation and discussion, from which a series of themes emerged. The material was (in some cases) selected around these themes. Then the young people undertook extensive research – spending days with archive material, visiting museums and exhibitions in London and listening to talks from a range of arts and heritage professionals.

How did archive material engage young people?

There’s an important quote from the project artist that I think sums this up…Writing in our journal Photoworks Annual, Helen (Cammock) said: “The ITO Collective tumbled into a melee of experience being asked to place themselves across time and place: imagine what it might have been like to have experienced some of the prejudice and pain, joy and love, sadness and forced invisibility that those who had come before them had experienced. It was a way of understanding what had come before, and the varying gradations of social change at different moments and in different places.”

As I said earlier, Brighton has such a vibrant LGBTQ+ community, but many young people weren’t yet engaging with this community. The archives helped bridge the gap between self and community - with the young people’s supported exploration of marginalisation and isolation, engaging with the personal stories of a community’s history and understanding that others had felt like they do,

Why was a creative element important?

It was always the intention that young people would create contemporary images that would be part of the archive. Photography played a central role in their learning experience throughout the project. From day one, they used cameras to chart their progress, document their research and articulate their ideas. Participants used photography both as a learning tool to support their enquiry, and as an artform, looking at contemporary practice, experimenting with ideas and developing highly accomplished personal portfolios. Exhibiting was an important additional showcasing platform for their work. The participants identified themselves as a collective soon after their first exhibition - when their artistic voices became more confident.

Any top tips for other institutions working with artists and young people?

Know and work with your artist’s practice and experience...Helen Cammock was instrumental in shaping the project (with myself and partners) and facilitating the programme. Helen’s practice uses a range of mediums including photography, film and performance to explore invisible histories, inequality and social justice. Helen worked as a social worker for more than ten years. She brought lived experience, a unique mix of visual arts skills and highly specialised youth expertise to the project, setting up a safe, creative space and instigating an enquiry-based approach using photography.

When working with young people, allow for organic development. We recruited two groups of young people (13-16yrs and 17-25yrs) some of our participants identified, others didn’t. We’d originally planned to work with two distinct age ranges, but after groups met, they were keen to work together, so the two became one. You can never underestimate the level of support young people need. This project allowed our participants to explore and develop their sense of self and identity. For some, this had a powerful impact and they required guidance and a lot of support.

The project involved collaboration between Photoworks, libraries, archives, community organisations, an artist and young people… Any advice on dealing with challenges in partnership working?

Give it time and be flexible. The main challenge was the project took much longer than anticipated! Initially envisaged as a 12 month project, it was extended to beyond 18 months. We had a brilliant mix of ambitious partners who each brought skills, expertise and resources to the project. There was a lot we wanted to achieve, and do well, so this took time.

It sounds like the project doesn’t only have a legacy, but continues to grow and influence…What happened next?

A lot happened next! And continues to happen. Three years later, three of the participants have recently been working as youth ambassadors on a new LGBTQ+ Photography Club we’re running, and they’ve been fantastic. In May 2018 some of the collective helped lead a pop-up photo booth at the Barbican Gallery, London as part of the Another Kind of Life exhibition and they’re also supporting a new LGBTQ+ programme we’re running. One young person worked on the hugely successful Museum of Transology at Brighton Museum and we’re now working on plans for an exhibition co-curated by the young people at Brighton Museum in 2019, as well as ideas for the next iteration of ITO.

FIND OUT MORE...

Visit the digital archive and read more: www.intotheoutside.org.uk

Follow: @photoworks_uk

ARCHIVE INSPIRATION...

LGBTQ+ heritage at locally-held archives, like the photo below, inspired young people as they created a new digital archive that shares and celebrates stories from LGBTQ+ young people in Brighton & Hove and beyond.

Image: Brighton Pride 1995. Courtesy Sally Munt and Queer In Brighton.

MORE IMAGES FROM THE 'ITO' DIGITAL ARCHIVE...

In addition to the selection of photographs from the Into The Outside archive featured on our website's homepage, we're delighted to share some more images below.

Image: Stars in Her Hair. Alfie, 2017. Courtesy of Photoworks.

Image: Together. Anisha, 2016. Courtesy of Photoworks.

Image: Anime. Mally, 2016. Courtesy of Photoworks.

Image: Varga, from the series Atlantis. Romy, 2016. Courtesy of Photoworks.

Thanks...

Our thanks to Juliette Buss (Learning & Engagement Curator), also to Chloe Hoare (Learning & Engagement Coordinator) and Helen Wade (Sale & Marketing Manager) at Photoworks, all the young people involved in Into The Outside and project artist Helen Cammock, and Sally Munt / Queer in Brighton for their permission to share the image 'Brighton Pride 1995'.

Juliette is a member of the Photographic Collections Network; we hope to share more news from Photoworks' Learning & Engagement programme soon.

If you have an idea for a blog post, please do get in touch: info@photocollections.org.uk.